The similarities between orangutans and humans and the closeness of our evolutionary history are often cited as important reasons to protect them. But what does this really mean, and just how closely related are we?

Genetic studies show that our genome-our hereditary information-differs by a remarkably small amount. Orangutans and humans both belong to the scientific order known as the primates, the group of mammals that contains all the monkeys, prosimians (the pre-monkeys) and apes living today. One of the oldest surviving mammal groups, the primate lineage is thought to go back at least 65 million years ago, when small, arboreal, insect-eating mammals, referred to as the Euarochonta, were beginning the process of speciation that eventually led to the primates we see today, one of the most diverse and varied groups of animals (Dawkins, 2004). Primates inhabit almost every part of the world, with the non-human species found mostly in tropical and sub-tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America.

While there isn’t one unique characteristic that defines a primate, there are a number of characteristics that are found throughout species of this order, including:

Primates are divided into two scientific sub-orders. The primates considered the most primitive, or those that have retained the most number of features of the ancestral primates, are classified as being Strepsirrhines. They include the lemurs of Madagascar; the galagos, pottos, and angwantibos of Africa; and the lorises of Asia. The tarsiers, monkeys, and apes are classified as Haplorhines due to their larger brains, specialized hands and feet, a wider range of facial features, and the lack of a rhinarium (wet snout).

Around 30 million years ago, the primates of the Haplorhini divided into two further groups, the Platyrrhini, which now consists of the modern-day New World monkeys of South and Central America, and the Catharinni, made up of the Old World monkeys of Africa and Asia, and the apes. This latter group split into two superfamilies at approximately 20-25 million years ago, as evolutionary pressures gave rise to drastic differences in the primate species. Modern-day Old World monkeys make up the superfamily Cercopithecoidea, The apes - the gibbons, chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, and humans - are the only surviving members of the superfamily Hominoidea.

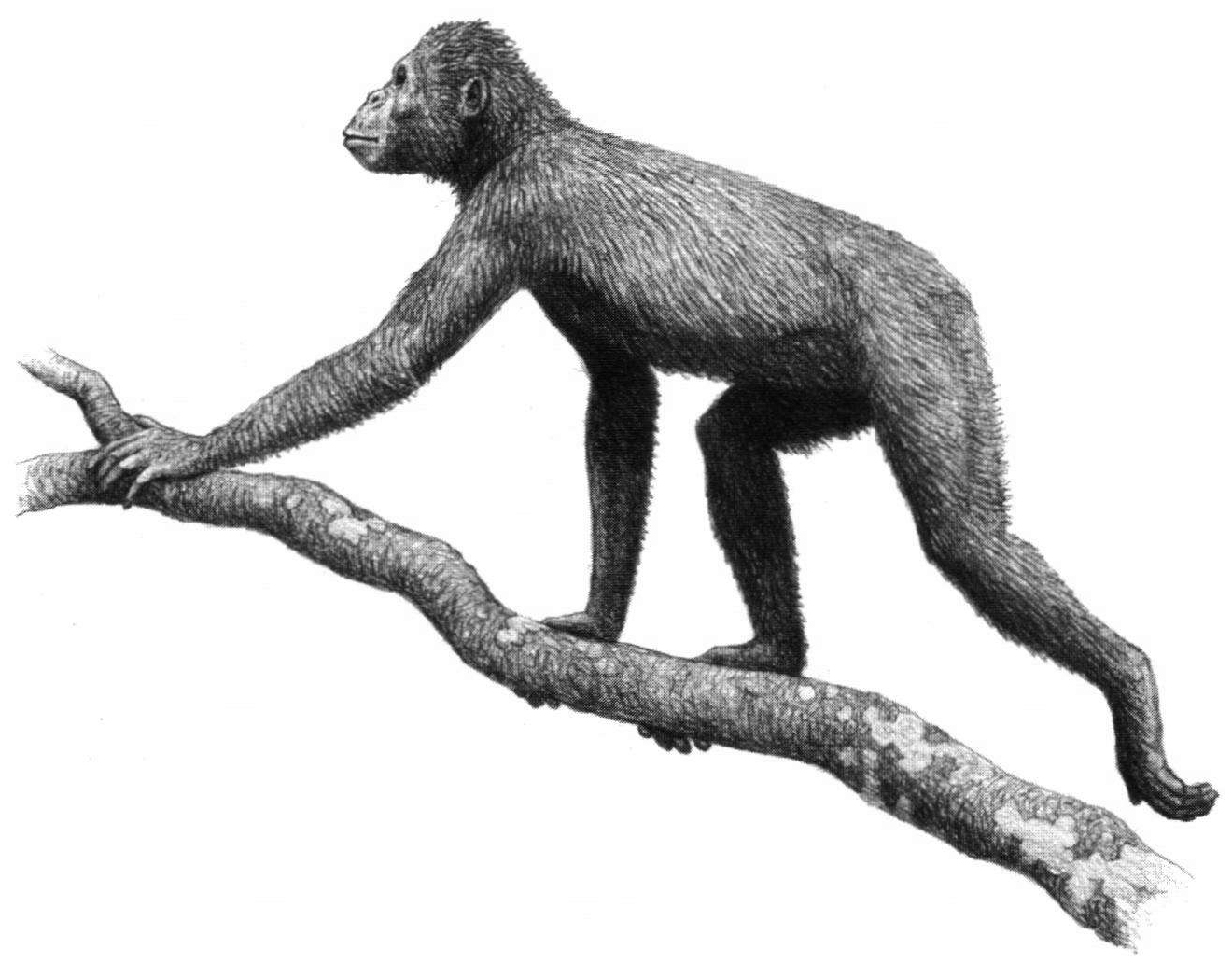

Proconsul reconstruction

Around 20-19 million years ago, a primate had evolved in central Africa that had characteristics of both Old World monkeys and apes. This primate, named Proconsul, included four known species and had a posture similar to that of a monkey. However, its lack of a tail, facial structure, and strong grasping capabilities distinguish it as an ape. Studies on the growth and form of fossilized Proconsul teeth show that this primate's life history was similar to that of a modern-day gibbon, with additional features of other apes and monkeys (Palmer, 2010). It's likely that the first apes evolved from a monkey-like creature that had descended to the ground and, through the process of evolution, lost many of their ancestral features, acquiring new ones as they adapted to their new environment. For example, a tail would be useful for a life in the canopy, aiding movement and balance. On the ground, a long tail is a hindrance to terrestrial movement and would be one of the first adaptations to disappear (Morris, 2008). Whether or not Proconsul is an intermediate between monkeys and apes and a common ancestor of present-day apes in the evolutionary tree is still debated. Regardless of this uncertainty, Proconsul is one of earth’s first known apes.

Between 9 and 17 million years ago, apes from the genus Dryopithecus were living not just in Africa, but were the first known species of ape to have migrated into Europe and Asia, giving clues to the migratory patterns of our ancestors (Palmer, 2010; Begun, 2004). Although there are variations in the five species of this genus, such as Proconsul, it resembled a monkey in many ways, but the bones in the forearm and elbow suggested it moved around in the treetops like an orangutan or gibbon. However, its skull formation is similar to that of the chimpanzee. Like all fossils, its evolutionary position is debated, but some scientists claim that Dryopithecus and its close relatives were the ancestors of all living great apes (Palmer, 2010).

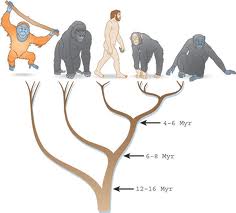

During this period (between 8.5-12.5 million years ago), three species of the genus Sivapithecus were living in the rainforests of Asia. Sivapithecus was around 1.5 meters in height, with many of its physical attributes resembling those of a chimpanzee. However, like an orangutan, it had a concave face with projecting incisors and large canines (Palmer, 1999). Fossils of this species have been found in Turkey, China, and Pakistan. Analysis of bone structure indicates they were adept at moving both on the ground and in the trees and fed on a diet of savannah grasses and seeds (Palmer, 1999). The genus Sivapithecus is now acknowledged as the direct ancestor of modern-day orangutans (Fleagle, 1999), and scientists believe that this line, the lineage that descended to modern-day orangutans, branched off from the line that descended to modern-day gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans around 12 million years ago (Palmer, 2010; Fleagle, 1999).

The orangutan is the only non-human great ape living in Asia today, but this development is relatively recent because another group of primates may have evolved from Sivapithecus (Fleagle, 1999) and lived at the same time as orangutans in what are now China, India, and Vietnam (Morris, 2008). Gigantopithecus lived between 300,000 to a million years ago, and was, as its name suggests, a giant. In fact, it's the largest ape ever known, with males weighing up to 540 kg - twice as much as a male gorilla (Morris, 2008). Scientists believe Gigantopithecus fed chiefly on plants and lived on the ground, walking on all four limbs like a gorilla (Morris, 2008; Galdikas, 1999). We don't know why Gigantophithecus died out, but it's possible that early man hunted it to extinction (Galdikas, 1999; Morris, 2008).

The orangutan is the only non-human great ape living in Asia today, but this development is relatively recent because another group of primates may have evolved from Sivapithecus (Fleagle, 1999) and lived at the same time as orangutans in what are now China, India, and Vietnam (Morris, 2008). Gigantopithecus lived between 300,000 to a million years ago, and was, as its name suggests, a giant. In fact, it's the largest ape ever known, with males weighing up to 540 kg - twice as much as a male gorilla (Morris, 2008). Scientists believe Gigantopithecus fed chiefly on plants and lived on the ground, walking on all four limbs like a gorilla (Morris, 2008; Galdikas, 1999). We don't know why Gigantophithecus died out, but it's possible that early man hunted it to extinction (Galdikas, 1999; Morris, 2008).

While the orangutan lineage was evolving in Asia, the primates that led to the modern-day African great apes and humans were still in Africa. Fossil evidence of ancestral gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos is sparse, due to the acidity of rainforest soil, which tends to dissolve bones, but fossils of early humans found in open savannahs and genetic mapping of the human and non-human ape genome offer a clearer picture of how the other great apes evolved.

The line that descended to modern-day gorillas is believed to have diverted from the line that chimpanzees and humans followed around 8 million years ago, with the chimpanzee lineage diverting from the human lineage at around 4 million years ago. The line that led to modern-day bonobos probably split from the chimpanzee line around 2.5 million years ago (Palmer, 2010). However, some scientists date the split between the human and chimpanzee lineages at around 7 million years, based on Kenyan fossils named Orrorin from about 6 million years ago that have distinctly human characteristics (Senut et. al., 2001).

The human (hominin) fossil collection is reasonably large, and although there is debate about the exact route the lineage from ancestral apes to humans took, the evolution from a quadruped covered in fur to the hairless bipedal ape we are today is well documented. Homo Sapiens emerged in Africa around 200,000 years ago, and spread throughout the rest of the world between 80,000-60,000 years ago (Palmer, 2010; Lockwood, 2007).

Begun, D.R. (2004). Sivapithecus is east, and Dryopithecus is west, and never the twain shall meet. Anthropological Science, 113, pp. 53-64.

Dawkins, R. (2004). The Ancestor’s Tale. Houghton Miffin, UK.

Fleagle, J.G. (1999). Primate Adaptation and Evolution- Second Edition. Elsevier Academic Press, USA.

Galdikas, B. (1999). Orangutan Odyssey. Harry N. Abrams, USA.

Lockwood, C. (2007). The Human Story. Natural History Museum, London, UK.

Palmer, D. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. Marshall Editions, UK.

Palmer, D. (2010). Origins- Human Evolution Revealed. Octopus Publishing Group Ltd, UK.

Redmond, I. (2008). The Primate Family Tree. Firefly Books Ltd, UK.

Senut, B., Pickford, M., Gommery, D., Mein, P., Cheboi, K. & Coppens, Y. (2001). First Hominid from the Miocene. Earth and Planetary Sciences, 332, pp. 137-144.