Almost 80% of the remaining orangutan population live outside of protected conservation areas (Jong, 2017), and they are often separated from each other in the fragmented patches of forest that remain after their larger primary forest habitat has been set ablaze to make way for plantations. Experts from the International Animal Rescue (IAR) Indonesia noted a recent increase in reported cases of human-orangutan conflict in the Ketapang district of West Kalimantan, which is consistent with the increase in wildfires in the area during that time (Pahlevi, 2020).

As the limited resources in these patches of forest are depleted, the apes are forced to flee in search of food, which greatly increases the odds of human-orangutan conflict at local farms and plantations. Many local farmers consider orangutans to be a threat to their livelihood and will resort to injuring or killing the apes for raiding their crops. “We hope people realize that when there’s no forest, it’s not only orangutans that suffer but humans also,” said Karmele L. Sanchez, the director of IAR Indonesia. “Having a home that’s safe from disruptions and has enough food supply is a solution to reduce human-orangutan conflict” (Pahlevi, 2020).

To decrease potential harm toward both animals and humans, authorities and other experts encourage locals to report all orangutan encounters to officials, who will then make arrangements to capture and remove the animal and assess whether or not it is best to release it into a protected area. As nearly 90% of translocated orangutans are healthy when initially captured, this practice could remove individuals who are vital to keeping the broader population stable and healthy (Cannon, 2021). The capturing of an orangutan is not without risk either, as the apes are susceptible to human-carried diseases that can prove fatal, and capturing an adult male orangutan can be a dangerous proposition for rescuers as well.

Recent research on the island of Borneo indicates that orangutans can sometimes survive in these human-altered, degraded patches of rainforests. “We figured out that the orangutans are using the better parts” of degraded forests, stated Greg Asner, an ecologist for the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO) at Stanford University in California. Orangutans prefer “tall trees and lots of canopy cover,” he added, emphasizing the existence of “more mature individual trees.” If these patches of forests offer adequate food and resources, and the apes are able to move throughout the canopy and build nests, then these forests are potentially viable habitats for orangutans. However, such preferences indicate that not all degraded tracts of forests are suitable for the animals (Cannon, 2017).

The existence of orangutans within these patches of forest and/or on plantations is sometimes mistakenly observed as evidence that the apes can still thrive with such massive alterations to their habitat, which could be used as a rationale to exploit primary forests. “It’s not true,” said Marc Ancrenaz, a biologist and director of the conservation organization, HUTAN. “Orangutans need the forest to survive,” he added, stating that allowing orangutans to live in potentially suitable degraded forest is merely “a feel-good exercise” and should not be the “default approach” (Cannon, 2021). “We still need to protect primary forests because there are a lot of other species that cannot really adjust to habitat degradation,” Ancrenaz concluded (Cannon, 2017).

IAR Indonesia will translocate orangutans only after they have assessed the impact that introducing a new animal will have on the ecology of the area. Argitoe Ranting, a field manager at IAR Indonesia agrees that “translocation is just a temporary solution,” concluding that the “real problem is with land-use change and forest degradation” (Pahlevi, 2020).

To counter such problems, IAR Indonesia assists farmers with strategies to minimize the damage to their crops, as well as investing in the development of alternative livelihoods. The primary goal is to avoid the circumstances that would require removing an orangutan.

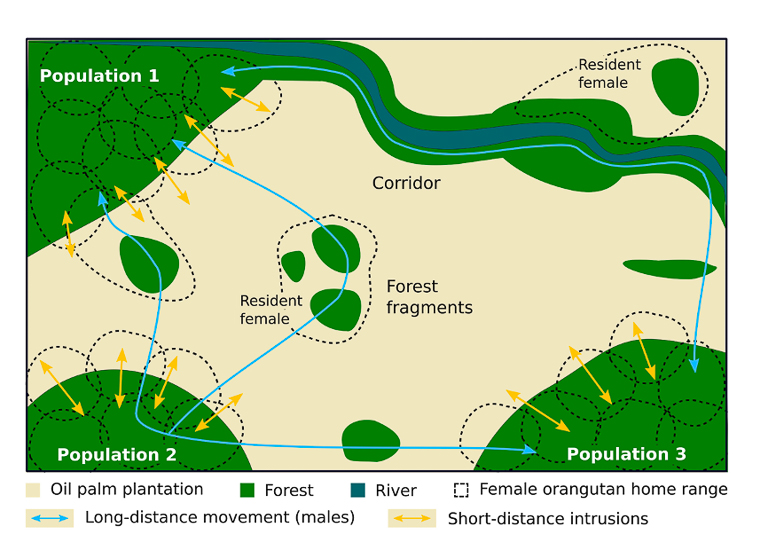

Findings in a recent study published by researchers from the University of York in the U.K. suggest that it’s insufficient to merely have sizable tracts of forest if they are fragmented throughout plantations. The study indicates that there could be a more sustainable way for the industry to progress if emphasis is placed on ensuring that high conservation value areas (HCVAs) are connected via forest corridors (also called stepping stone patches), and the goal is for plantations certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to eventually adhere to the organization’s new guidelines as an industry standard (Crothers, 2019).

Sarah Scriven, a co-author of the study, stated that forest corridors “may facilitate the movement of forest species through the surrounding plantation matrix.” Scriven also believes that the solution is to have a coordinated effort among the plantation owners. “[These plantations] may otherwise act as a barrier to movement between the forest set aside and other areas of forest within the wider landscape,” Scriven said (Crothers, 2019).

As far as the “human” part of the conflict equation, recent fieldwork suggests that, although orangutans are a popular international conservation cause, local communities do not necessarily share the sentiment for the species’ welfare.

“The running joke among anthropologists is that you take these posters to guys in a longhouse, and they go, ‘Right, that’s today’s menu.’ This is something they’ve been doing for a long time, and they don’t see why they should stop just because the state says so. . .people do wonder why animals get so much more cash and attention than the humans who live in the same areas,” said social anthropologist Liana Chua, who leads POKOK (Project On the Keys to Understanding Orangutan Killing), which aims to reduce the killing of orangutans through pronounced engagement with local people. Chau added that orangutans are “much less visible where they actually live” and that “conservation priorities may conflict with, or take a back seat to, local priorities” (Jong, 2018).

In the end, Chau believes that one of the significant problems with traditional conversationism is that it is implemented based on a separation between humans and nature, and that “such a separation doesn’t necessarily exist. . .we need to get beyond the ‘parks versus people’ model” (Jong, 2018).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Cannon, J. 2017. Orangutans find home in degraded forests.

https://news.mongabay.com/2017/07/orangutans-find-home-in-degraded-forests/

Jong, H. 2017. 80% of Bornean orangutans live outside protected areas. https://news.mongabay.com/2017/09/80-of-bornean-orangutans-live-outside-protected-areas/

Jong, H. 2018. Small farmers not ready as Indonesia looks to impose its palm oil sustainability standard on all. https://news.mongabay.com/2018/04/small-farmers-not-ready-as-indonesia-looks-to-impose-its-palm-oil-sustainability-standard-on-all/

Crothers, L. 2019. Connected forests key to more sustainable palm oil industry: report. https://news.mongabay.com/2019/09/connected-forests-key-to-more-sustainable-palm-oil-industry-report/

Pahlevi, A. 2020. Burning and bullets: Forest fires push Bornean orangutans into harm’s way. https://news.mongabay.com/2020/02/burning-and-bullets-forest-fires-push-bornean-orangutans-into-harms-way/

Cannon, J. 2021. Forest patches amid agriculture are key to orangutan survival: Study. https://news.mongabay.com/2021/02/forest-patches-amid-agriculture-are-key-to-orangutan-survival-study/

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This article was researched and written by Todd Cravens, OURF Volunteer.