by Gary L Shapiro, PhD, President OURF

In late 2011, as I walked down the 200-meter boardwalk to the Sekonyer River, my eyes welled up with tears. It was a moment filled with profound emotion as I bid farewell to Princess and her fifth offspring, Putri. Little did I know that this would be the last time I laid eyes on this remarkable orangutan. Today, all that remains are memories, etched into my mind as I reflect on the nearly two years I spent raising her as my adopted daughter and student during the late 1970s. This journey took place as she transitioned from being an ex-captive orangutan to a free-ranging resident of a forested peninsula in Indonesian Borneo.

This is the last photograph I ever took of Princess and Putri as they walked into the forest -(c) Gary Shapiro

My journey to becoming Princess's adopted father started a half-century ago when I formed my first close relationship with a captive orangutan named Aazk at the then Fresno City Zoo (now Chaffee Zoo). I was a graduate student conducting pioneering research on the early linguistic capabilities of this species, and Aazk was my student. I was given the extraordinary opportunity to enter the cage with her (yes, an old-fashioned chain-link fence cage) and spend an hour or so each session interacting with her before the zoo opened, all in the name of science. Like all juvenile great apes, Aazk was interested in playing, so she treated our interactions as a game. During that time, I was able to employ basic psychological conditioning techniques to have her associate plastic children's letters with items of interest, such as chunks of apples, bananas, and oranges. Over time, she could select the right symbol in a matching situation, and eventually, as she mastered the simple associations, the task was made more difficult, requiring her to construct sentence-like sequences of symbols to request items or activities. While I used the information I collected over a nearly two-year period to earn a Master's degree, the time I spent with Aazk showed me something about the nature of young orangutans within the zoo setting. Some of what I saw suggested to me that orangutans have sentient qualities, not unlike those we possess as humans.

Here I am tickling Aazk between moments of study.- (c) Gary Shapiro

When I finished my degree and wasn't accepted into medical school, I decided to continue my education and interest in great ape linguistic abilities by traveling to the center of the USA to the University of Oklahoma. There, the comparative psychologist Roger Fouts established a program for teaching and studying sign language acquisition and use by captive chimpanzees, including the world-famous Washoe, the first nonhuman to become adept at propositional communication using signs rather than vocal language. Roger helped train Washoe in Reno, Nevada and was her caretaker and friend. Washoe was part of a colony of captive chimpanzees at the Institute for Primate Studies, where she felt very different from those of her own species surrounding her. She would call them "black bugs" when asked by Roger.

Here I am holding the playful and diminutive Mac.- (c) Gary Shapiro

I got to know Washoe during my first two years in Oklahoma and even went on walks with her and other chimpanzees like little Mac, who were generally even-tempered and manageable. I learned the rules of working with chimpanzees and was in the middle of my own doctoral research project when Roger called me on July 5th, 1977. He mentioned that the orangutan researcher Birute Galdikas was looking for someone to teach sign language to an orangutan at her Borneo research station, as well as run the station when she and her husband were away. I immediately said yes, and a year later, I was headed up the Sekonyer River into Tanjung Puting Reserve for the first time. My destination was Camp Leakey, named after the famous paleoanthropologist who encouraged her to study wild orangutans shortly before he passed away. He was also known for supporting Jane Goodall's and Dian Fossey's research on wild chimpanzees and gorillas, respectively.

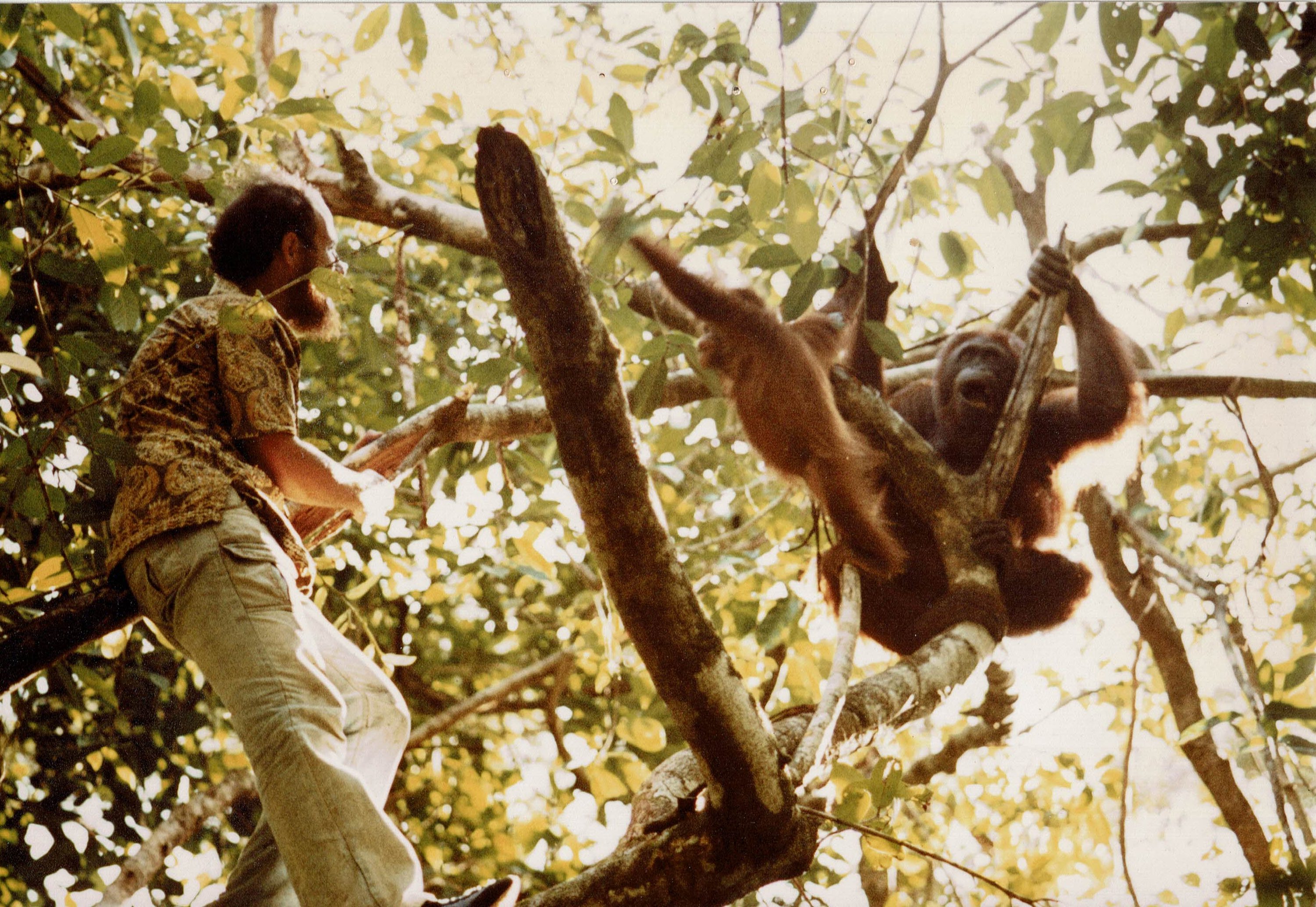

Here I am in a tree with Siswoyo and Siswi - (c) Gary Shapiro

Over the course of my two years at Camp Leakey, I was privileged to have befriended numerous ex-captive orangutans and taught a half-dozen individuals a variety of signs that they would use to describe objects and request activities of interest. Among them were the adult female orangutan Rinnie, my orangutan daughter Princess, and her cohorts Pola, Hampas, and Rantai. I was able to study some of the factors influencing how quickly they learned signs, and while I engaged in basic conversations with them using sign language, my doctoral research focused on sign learning. Significantly, this was the first sign language study with any species of great ape that took place in their natural habitat. When I wasn't conducting my research, I was keeping Camp maintained, caring for the sick orangutans, and trying to stay healthy. At the end of the two years, I had enough data to develop my dissertation, but more importantly, all my students continued their journeys back to the wild or remained free-ranging, bi-cultural orangutans in and around Camp Leakey.

Relaxing between lessons with Princess, student Toto and orangutan Pola. (c) Gary Shapiro

I also went to Borneo and Camp Leakey as a biologist/zoologist who had an appreciation for the abundant biodiversity of the region. I came to see that this remarkable protected ecosystem was unique but increasingly under threat, as were the wild orangutans living both inside and outside Tanjung Puting Reserve. We were receiving confiscated orphaned orangutans whose mothers were killed as pests or simply to obtain the infant orangutan to be sold on the black market. I saw evidence of illegal activities around the reserve and within Galdikas's 50 km2 study area. We both came to understand that more had to be done to ensure the integrity of the reserve and to fund the long-term research. When I returned to the USA in 1980 with Galdikas’s encouragement, I helped start the process of creating the first orangutan advocacy group which became the Orangutan Foundation International (OFI).

For 18 years, I served as Vice President of the OFI and supported Galdikas in running the organization. Along the way, I learned a great deal about the politics and other complexities of conservation work and operating a nonprofit foundation. I grew increasingly disenchanted that the number of confiscated orangutans was growing, and not enough was being done to address the root causes of the problem - lack of education, fear, apathy, poverty and greed. In 2004, I left OFI to focus on this long-term challenge. With my wife, Inggriani, we co-founded the Orang Utan Republik Education Initiative with a mission to save wild orangutans through education and other innovative programs that inspire people to take action. If you are reading this article, you already know about the Orang Utan Republik and my passion for helping orangutans like Princess as well as the people of Indonesia whose actions will impact the long-term outcome for the species. You know about our Orangutan Caring Scholarship program, our Community Education and Conservation Program in North Sumatra, and our partnership with The Orangutan Project.

Over this half-century journey with the “persons of the forest” I have come to recognize that orangutans are persons and thus deserve legal personhood status. Such status would certainly afford them more rights and protections as individuals and as a species. If we compare their early neurophysiology, their cognitive development, their self-awareness and theory of mind, their sentient qualities, and their emotional abilities, orangutans, indeed all the great apes, are not unlike humans. In 2014, an Argentine court granted personhood status to Sandra, an orangutan living a solitary life in the Buenos Aires Zoo based on the argument that she displayed cognitive and emotional abilities similar to those of a human being. Animal rights lawyers in Argentina convinced the court she was suffering and should be released from her captive situation under the writ of amparo (similar to the writ of habeas corpus). I was fortunate to have been asked as one of three expert witnesses to represent Sandra in court via Skype. The court's decision to adjudicate the case was rooted in the idea that Sandra deserved legal rights and protections as an individual with these capacities, including the right to live in a more suitable environment and better conditions. This landmark ruling was a significant step in recognizing non-human animals as beings with legal rights in Argentina. Sandra eventually was transferred to the Center for Great Apes, a sanctuary with other orangutans (and chimpanzees) in Florida. While she lost her personhood status by entering the United States, she gained a much better life in her new home living happily together with a male adult orangutan named Jethro. I wonder when the conservative legal system in the United States will eventually recognize the personhood status of orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas. It is important to have these conversations and to continue to advocate for better conditions for all great apes.

A half-century is a long time to reflect. My long-awaited book, “Out of the Cage” will be released in September 2024 and will recount many stories in greater detail of my fifty-year love affair with orangutans including my conversion to being a conservationist, and my thoughts about orangutan personhood and Sandra’s story. It will be available through The Mad Duck Coalition- at tinyurl.com/outofthecage. In addition to telling my story, my hope is that the book will inspire others to see orangutans in a different light and to take up the cause for a world without orangutans would be a poorer world indeed.